War cuisine: food in Italy during the world wars

The twentieth-century wars witnessed a series of crucial revolutions in the field of food organization, both military and civil, which, at the same time, much involved the...

The twentieth-century wars witnessed a series of crucial revolutions in the field of food organization, both military and civil, which, at the same time, much involved the...

In the “Regimen Sanitatis” of the Codex Atlanticus (F 213v), Leonardo da Vinci registers the hygienic precepts and advice for healthy living, followed by the rules of...

The plague described by Manzoni arrived in Milan in the autumn of 1629, spreading gradually in 1630. In May of the same year, everything fell apart, so much so that people...

The subtleties of nature and health One of the most significant female figures of the early Middle Ages, Hildegard, lived along the Rhine River, in the tract that separates Hesse...

“Autumn. We already heard it coming / in the August wind, / in the September rains / torrential and weeping…”, this is how Vincenzo Cardarelli sang this...

“Let him bring huge lampreys or enormous salmons or pike, without letting it be known. A good eel is hardly bad, shad or tench or some good sturgeon, cakes or stuffed...

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food....

In early June, more than 2300 years will have passed since the death of Alexander the Great; in fact, the Macedonian king died in 323 B.C., at 32, after a very short illness. The...

At the port of Livorno, no one had noticed the rustling of that bulky cloak. Blessed by the most desiring stars, the curved shape of Settimontano Squilla was embarking on a...

The rigorous and meticulous Immanuel Kant, the milestone of modern philosophy, pleasure and pain of high school students, also had its own detailed “gastronomic...

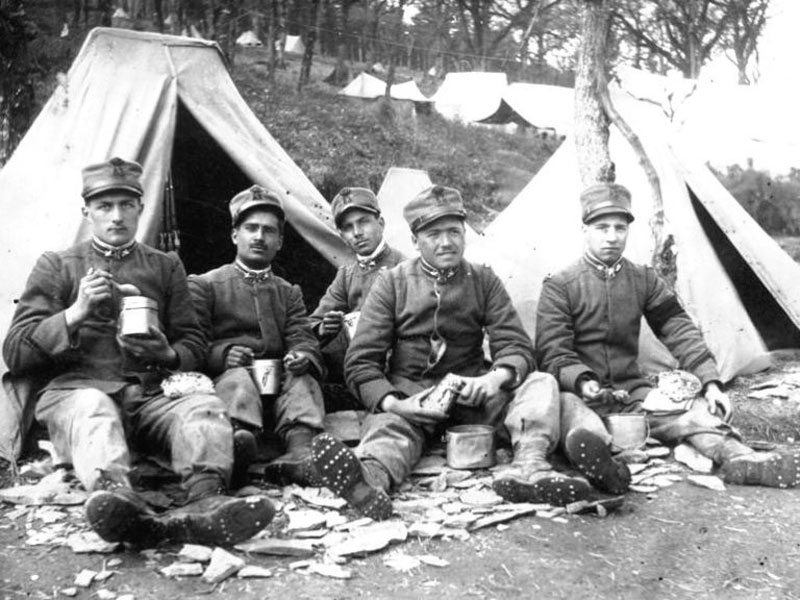

The twentieth-century wars witnessed a series of crucial revolutions in the field of food organization, both military and civil, which, at the same time, much involved the population, who had to suffer the consequent food crisis related to conflicts.

In this period, they issued several unconventional publications, often in the form of pamphlets, dealing with food in wartime on its many sides, both for the soldiers at the front and for civil society.

The First World War began with the belief the warring nations shared that war would be a “blitzkrieg”: no government, therefore, troubled about ensuring food supply for the army and the population in the long term. However, serious problems for the livelihood of the military and civilians soon arose. Italy, a recent and poorly industrialized nation, was forced to make immense and urgent sacrifices to support the provisioning of the one million conscripts and the feeding of the civil population. Eating habits had to be forcibly changed while devising alternative production technologies and consumption. They asked the whole country to support the war effort.

The armies had to provide the distribution of the rations to the front line through a logistic network. A system of warehouses allocated along the entire front line. Fixed and mobile kitchens; containers suitable for carrying cooked food in the inaccessible areas along the front. Portable stoves and mules or by resorting to the logistic services and transports on shoulders. The porters, in some cases, were also women.

Rations arrived at their destination late and sometimes many days later. The quantity compensated for the poor quality of food. For many soldiers, coming from regions often on the verge of survival, the meal provided was still flavourful than whatever they used to eat at home, where meat was a rare food for them, even if the quantity did not equate to quality.

The conflict also had a profound impact on the food industry. Frozen meat, canned meat, lard and salted meat came from South America. The tinned food, intended for the army, were decorated with figures praising their motherland and propaganda slogans. Museums still today keep several of these metal containers. Along the trenches of the broad front, you can still see many metal boxes abandoned on the ground. During the war, factories produced about 200 million cans, and by the end of the conflict, there were countless tinned meat cans left in the warehouses. They distributed canned products purchased by Italian families, adding them to their eating habits.

The Italians imprisoned in various areas of Europe, in the three years 1915-18, were almost 600,000; of these, about 100,000 died of tuberculosis, hardship, and starvation.

In the prison camp of Celle, near Hanover, between 1917 and 1918, they imprisoned almost three thousand graduates of the Italian army. In this context, two exceptional recipe books, written by the officers Giuseppe Chioni, from Genoa, and Giosuè Fiorentino, from Sicily, interned there, have come to us.

The recipe book springs from a mutual exchange of memories and desires. It shows a transformation “from warriors to cooks”, as Montanari points out. In some way, food constitutes, for the prisoners, an element of resistance to annihilation caused by forced segregation and hunger. These are “team” works. Arte Culinaria (Culinary Art), the cookbook compiled by Giuseppe Chioni in collaboration with Luigi Marazza, shows a great effort, even formally. In Culinary art, there are 414 recipes, divided into sections, each introduced by a dedicated drawing, constituting a comprehensive picture of national cuisine.

As the historian John Dickie writes, “… the extraordinary and moving fact is that the much hungry prisoners of the Celle concentration camp managed to create a text capable of challenging Science in the kitchen by Artusi as the best recipe book of Italian cuisine ever written until then”.

It is the most incredible of cookbooks, which narrates an allegedly minor page of the Great War. Those memories, which keep the prisoners of Celle alive, are a sort of break from the brutality of the concentration camp achieved with the imagination and the memory of the home kitchen.

According to food-historian Massimo Montanari, unlike the 1939-45 conflict, the Great War left no downside traces in the renewed food balance. Indeed, they believed it constituted an opportunity for millions of peasants at the front to savour even in the context of the trench, many foods generally precluded to them: meat, pasta, wheat bread, wine and coffee. Besides these, families sent food to their soldiers. Such provisions, which reflected the different domestic and regional traditions of the region of provenance, were shared among all.

The war gave people the opportunity to meet, for the first time, cultural traditions and food, different from their own, contributing to the strengthening of an Italian food model, a network of knowledge and practices from different local regions, which meet and influence each other. If the Second World War left heavy consequences on malnutrition, the First War, considering nourishment, was different. The Great War did not completely eradicate the subsistence guaranteed by the rural economy. There were hardships, not hunger. On the other hand, famine hit the entire population in the Second World War, regardless of wealth. Before the war, Italy had different styles of food. With the advent of the war, the mixing of Italians from various regions produced an exchange of local recipes. There was a gastronomic unification of Italy and the birth of Italian cuisine. Some companies experienced enormous economic growth during and after the conflict, and the pasta and canning industry developed.

The first total war in history had a profound impact on the life inside each country. For the first time, civilians became protagonists of the war. The conditions in which the people found themselves were increasingly gruelling, with drastic consequences on the birth rate and the spread of diseases.

The Italians’ diet had already begun to deteriorate before the outbreak of the Second World War. In the early 1930s, problems started with bread. Despite the efforts of the Fascist Regime, agricultural productivity remained low, especially in the South. The prices of pasta and white bread got higher; it is no coincidence that the fascist propaganda discredited their consumption favouring rice.

Many were the issues that Italians encountered in securing food, especially after they introduced the ration card. Furthermore, the growth of the black market, born as an aid to the population, in some cases, sidetracked towards the path of personal enrichment.

In 1935, Italy suffered “unfair sanctions” due to the colonial war in Ethiopia. Autarchy also enters the kitchen.

Autarky, however, initially was not a hindrance for the Italians. The regime managed to disguise the current situation very well by implementing a programme of slogans against the excessive consumption of food and favouring a greater consumption of fish and vegetables instead of meat. The circumstances became increasingly critical year after year, also to respond to the needs of the army. The relation between the fascist regime and nutrition had always been very close. Together with autarky and rationing policies, Mussolini implemented a strategy of war against waste. They published articles and manuals that spoke to women informing on how to use everything, bring something tasty to the table, cooked creatively and well served. Here we identify the exceptional progress of those times, the ability to re-propose the same raw material in multiple ways. Until the early twentieth century, on average, people knew two or three cooking food methods because there were various products. When products lacked selection, recipe books full of alternatives were born to prepare the same food, in new ways, with a typically Italian spark of genius.

Despite the measures taken by the government and the propaganda interventions of the regime, the rations were no longer able to guarantee even bare survival and cover the daily caloric needs. In this circumstance, to bring something to eat for their family, women were forced to perform miracles. At the time of the armistice of 8 September 1943, the feeding conditions of the Italians was collapsing. With the Allies advancing, however, the situation did not improve, at least in the immediate future. They witnessed the collapse of the supply system in the South, which will recover just after the war ended. However, even in the Centre-North, things were no better for all the parties involved.

The suffering of the population become enormous, especially in the cities. Even in a situation of daily danger, the population exasperated by hunger did not hesitate to protest.

«The dreams of the partisans are rare and brief, dreams born from nights of hunger, linked to the history of food that is always scarce and to share among many: dreams of pieces of bread bitten and then closed in a drawer. Stray dogs must have similar visions, of gnawed bones and hidden underground«, wrote Italo Calvino.

With the Second World War, food for civilians became a daily torment, while for the partisans, the situation was even more arduous. Food was a dilemma to face every day for those who fought and could not count on official military supplies. We read of food shortage in the messages exchanged between the various partisan brigades. Food was no less significant than munition to fight. Hunger is a constant that accompanied the partisans, ending up the songs of the Italian resistance.

Nutrition and moments of sharing food represented the central opportunity to socialize, discuss, and be companions, in the complete sense of the term. On the other hand, the etymology of the word “companion” derives from one of the simplest gestures of humanity: the sharing of bread.

In the war years and, perhaps even harder, in the post-war period, the number of single ingredients available, many of which contained essential nutrients, drastically declined. They tended to disappear or became rare because of costs or complete lack of production or territorial diffusion. The recipe books of the period responded in the only possible way to this issue: the quest for new calories source for the preparations. A meagre, really poor cuisine. Pure subsistence.

The crisis, the precarious economic conditions and the hunger brought by the Second World War did not cease with the end of the conflict. We must wait until the 1950s to begin to glimpse the first stirrings of that economic boom that would then overwhelm Italy and other industrialized countries, giving way to long-awaited technological development and economic growth. Until then, poverty and hunger continued to be protagonists.

After the Second World War, mainly during the 1960s economy booming, the quantity and quality of food consumption increased thanks to the innovations in science and the spread of well-being. Despite this, the fear of hunger remained. It peeps out whenever a crisis overwhelms us, be it of an economic, political or health nature. It is the fear of starvation that still drives us to fill refrigerators and pantries.

Food is itself an instrument of war, a weapon that feeds the vulnerability of nations. Its control and peoples reduced to starvation have always been instruments of war as powerful as bombs, even in peacetime.

ILARIA PERSELLO